Miracu(less)

It’s good to be back folks. You have no idea what a lousy six months stretch of poor relative performance numbers can do to a bond manager who bases his entire ego on performing miracles year after year. Forget about those Allianz mega bucks. They’re just numbers on a broker’s statement. Toss away those scrapbooks full of magazine articles and trophies proclaiming PIMCO to be the king of the bond hill. The past is just a goodbye when the numbers are runnin’ bad. Anonymity, not notoriety is the watchword. You mope, hang your head, chew out your wife for no reason at all, wake up at 3:00am, then take the stairs instead of the elevator up to work. It must be the equivalent of PMS except in this case it’s the “Performance (is) Missing Syndrome.” Don’t talk to me, don’t try to be nice to me, Just Leave Me Alone! Trouble is, it doesn’t go away after a week or so – it just hangs and hangs and hangs on until the numbers go sunny-side up instead of scrambled

But I’m here to tell you folks that my eggs are being served in a different style these days, and just in the nick of time, I suppose. Some of you were beginning to have doubts. The competition was all abuzz with the “what’s wrong with PIMCO” routine and the “too big, too rich” pat answers that no one could blame them for. My wife, Sue, knew better though. Placing her bitten head back onto her shoulders for the umpteenth time, she confidently proclaimed that the numbers always came back – it was just a question of time. “You know what you should do,” she said, “is to take the month off, come back, and everything will be just fine.” Her version of the “take two aspirin and call me in the morning” antidote I suppose. Well, I did do some of that – an Alaskan cruise, the golf course in the afternoons, some rose smelling instead of flower bed trampling – and lo and behold the “numbers” came back! Forget those stairs, I’m riding the elevator again.

Such miraculous transformations, however, come with no guarantees for future performance. The tide comes in and the tide goes out as they say. Still in this business, having a set of tables to gauge the ebb and flow of the global economy and its investment markets can be an immeasurable guide in avoiding long-term, as opposed to six-month performance disasters. PIMCO’s tables have always had a secular theme to them, and that secular theme in recent years has been dominated by the question of productivity and its resurgence in a “New Age” economy. “Is it different this time or not?” is the essence of this biggest of all investment questions, and while our recent Secular Forum in May of 2001 recognized U.S. productivity as the global economy’s “weakest link,” that phrase still begged the question of how weak of a link, or conversely – how strong this New Age tide. Some of your eyes may already be glazed over at the seemingly incessant reintroduction of this somewhat boring economic conceptual conundrum. Who really gives a hoot you might submit and I couldn’t blame you if you did. Still, as I suggested a few sentences back, it is the big Kahuna of investment questions. Picture a craggy old Jack Palance in City Slickers holding up his index finger to a befuddled Billy Crystal. “Just one thing,” he says, “you must know just one big thing.” The future level of productivity in our New Age Economy is the investment world’s “one big thing.”

Its supreme importance derives from the fact that almost all of our markets in some form or fashion are valued based upon a rolling assumption of how large or how small productivity will be in future years. NASDAQ 5000 in March of 2000 was made possible by sugarplum assumption of 4, maybe 5% growth rates in productivity for as far as the eye could see. 5% productivity increases year after year can do wondrous things for corporate profits so who was to quarrel with P/E ratios of 200 x or more. Who in fact would quarrel with dropping the concept of P/E ratios altogether and substituting the concept of price/sales because in a high productivity world, sales inevitably would lead to profits, which inevitably would lead to soaring stock prices. But it wasn’t just the valuation of stocks that thrived in a high productivity “new age” economy. Because productivity increases kept inflation down, interest rates were affected as well. Long-term bond prices and productivity, it seems, were Siamese twins. One couldn’t move very much in one direction without the other responding in a similar fashion. Likewise, the fate of a strong dollar depended on the belief that the U.S. economy and its investment markets offered superior returns to those in alternative economies. And those excess returns of course were predicated on the belief that our productivity – whether it came from deregulation, increased investment, or simply, good ole’ U.S. of A. know-how – was far and above levels experienced in the rest of the world. I could go on and on. How about the trade deficit? It would not be tolerated at such exorbitant levels unless our foreign creditors believed we could pay it all back and then some by growing faster than everyone else. How about our budget surplus? It wouldn’t exist unless the productivity miracle created 4% GDP growth and capital gains as far as the eye could see. And how about… and how about… Yeah, one big thing. It’s simply the one big thing. Tell me the answer and I’ll tell you where the stock market’s going, where interest rates belong, where the dollar is headed, the fate of the budget surplus, the future moves by Alan Greenspan, and the next President of the United States. Big. Big thing.

All right. So, I’ve set the stage. The audience is all tense and excited, on the edge of their seats for sure – who wouldn’t want to know the answer to the one big thing? The only question it can’t answer I guess is whether Gary Condit did it or not and who knows, maybe there’s something in there for this summer’s most important question too.

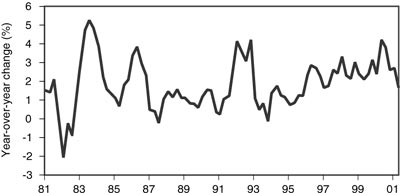

How best to answer it? Well aside from the precautionary disclaimer of “there are few answers – only more questions,” and a reference to our more academic May Investment Outlook, an obvious approach seems to be to analyze whether the productivity “miracle” of recent years was cyclical and therefore ephemeral, or secular and thus perpetual. A first step towards the answer would be to use and trust your own eyes. The following chart displays recently downward revised productivity numbers for the last few years within the context of the past several decades.

Cyclical Slide in Productivity Growth from a Lower Peak

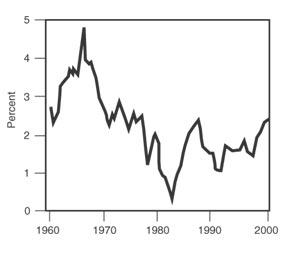

Tell then to my eye there were several miracles in the 1980s and a short-lived miracle in the early 90s and another miracle towards the end of the century. But so many “miracles” sort of dilutes the relevance of the phenomena doesn’t it? The fact is that in the last 10 years the compounded annual change in non-farm productivity has been 2 percent. Over the last 45 years it’s been 2 percent. Call it the 2 percent solution if you want to but don’t call it a miracle. To be fair, as seen in the following chart, which displays productivity as a five year moving average, the U.S. just recently attained 5 year growth of 2.3% but that only looks impressive in comparison to the cyclical depths of the recessions in the early 80s and 90s. It’s certainly not miraculous when compared to the late 60s, which showed 5 year averages of 3% .

Productivity Changes 5-Year Moving Average

All right, already – enough, enough. It must be obvious to you by now that when Al Michaels screams, “Do you believe in miracles?” that I yell a resounding, “NO!” in response, even if the USA keeps beating that 1980 Russian hockey team in replay after replay. No, I don’t believe in miracles, I don’t believe in “it’s different this time.” Look at the facts Ma’am as Jack Webb used to say. Look at the charts. Productivity increases in the late 90s look cyclical, not secular.

But even if you agree with me, “what oh what” you might ask does this have to do with a bond manager climbing stairs instead of riding elevators? Well, almost everything – like I said a few paragraphs ago. Because in the first few quarters of 2001, the bond market was clinging to this belief in a productivity miracle and therefore a quick and significant economic recovery once the dark days passed by. A “V” shaped recovery, not an “L”, nor a half “H”. PIMCO had bet otherwise. PIMCO had faded the New Age Economy. We had placed our bets on interest rates and Greenspan going low and staying low, not just in 2001 but in 2002 as well. We had placed our bets on a weaker dollar. We had placed our bets on European interest rates mimicking U.S. trends with a six-month lag. But none of this was going to happen as long as the “market” embraced the “V” and the New Age economy instead of the half “H” and the normalized one. Then suddenly, so suddenly, the markets began to change their minds or at least to have doubts. Yours truly began to hit elevator buttons instead of his head against the wall. Sue’s prophecy came true – “take the month off, come back, and everything will be just fine.”

Fine for now, but the tide comes in, the tide rolls out. Timing the tide though and outperforming the bond market in future quarters and years will depend on secular, not short-term thinking. It is what defines PIMCO– and the secular big thing du jour revolves around the question of productivity and its future trend both here in the U.S. and globally. Get it right and you will correctly answer questions about stocks, bonds, currencies, the budget surplus and perhaps even the “Honorable” Gary Condit. Get it wrong and you head for the stairs. I believe in normalized 2% productivity and low short-term interest rates for the next several years. My (and your portfolio’s) fate depends upon it. And just so that I don’t leave you hanging – here’s a brief table of probable outcomes for other investment “things” under a 2% productivity scenario.

Future elaboration on the above will appear in next month's Outlook. Until then...keep riding elevators.

William H. Gross

Managing Director

Disclosures

No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form, or referred to in any other publication, without express written permission.

This article contains the current opinions of the author but not necessarily Pacific Investment Management Company, and does not represent a recommendation of any particular security, strategy or investment product.

The author's opinions are subject to change without notice. Information contained herein has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed.

This article is distributed for educational purposes and should not be considered as investment advice or an offer of any security for sale. Past performance is not indicative of future results and no representation is made that the stated results will be replicated.

Copyright ©1999-2003 Pacific Investment Management Company LLC. All rights reserved.